|

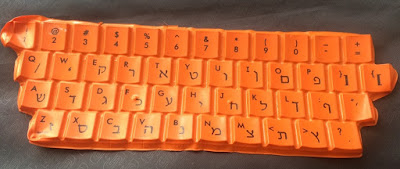

| Modern Ivrit keyboard |

The collection of letters used for writing is known in Yehudit (modern Ivrit; which we should not, but do call: "Biblical Hebrew") as the Aleph-Bet, these being the first two letters in the list; it is called the "alphabet" in English for the same reason, though it would be more obvious if we called it, as children do, the "a-b-c"; Alpha and Beta are the first two letters in the Phoenician alphabet, which became the Greek alphabet, which became the Roman alphabet, which is still the alphabet of most European countries, and those which use European languages. As we shall see, the two words are the same, or at least stem from the same root, as both Greek and Yehudit are developments of the Ugaritic alphabet, created by the Phoenicians in what is today the Lebanon.

|

| Ugaritic alphabet |

A Brief History of the Alphabet

Hieroglyphs and cuneiform and the picture-words of the ancient Chinese were the earliest known method of expressing language in a visual form; but none of these can be called alphabets.

Not earlier than 2,000 BCE: The first alphabet in a form that resembles the one we know was probably invented in Mitsrayim (Egypt) as a simplification of hieroglyphs; perhaps by soldiers who were formally illiterate, or by clerks needing a more colloquial mode.

Not earlier than 1000 BCE: Properly developed by the Phoenicians of Tsur (Tyre) and Tsidon (Sidon) around the time of King David, and immediately adopted by the Beney Yisra-El. The Aramaic language replaced the Hurrian pre-Yehudit from 586 BCE, but continued to use the same alphabet, simultaneously travelling east into the Brahmic scripts of India and Burma, and the Devanagari scripts that fed Cambodian and other south east Asian variations. The arrival of the alphabet in Bav-El (Babylon), with the exiles from Yehudah, was the likely cause of the end of cuneiform.

800 BCE: The Greeks adopted the Phoenician (now called the Ugaritic, from another Lebanese town, close to Byblos, itself the much more likely "real" site of the Tower of Babel). Unlike the Beney Yisra-El, who took the meanings of the Phoenician words as well as their letters, the Greeks ignored their meanings for the most part, and made some minor variations of pronunciation. Nevertheless we can see how the Phoenician spawned both alphabets, and how the Greek then spawned both the Roman and Cyrillic alphabets that we use today. Residual too are the names of the letters: alpha, beta, gamma, delta etc in the one; aleph, bet, gimmel, dalet etc in the other.

700 BCE: The Etruscans adopted the Greek, again with some minor variations.

600 BCE: The Romans adopted the Etruscan, again with some minor variations. It is the Roman alphabet that we still use today in English, French, Spanish, German etc.

300 BCE: The Celts developed their Runic alphabet from the Etruscan.

900 CE: The Greek alphabet, in its last flowering, gave birth to the Cyrillic alphabet still used in Russia.

600 BCE: The Romans adopted the Etruscan, again with some minor variations. It is the Roman alphabet that we still use today in English, French, Spanish, German etc.

300 BCE: The Celts developed their Runic alphabet from the Etruscan.

900 CE: The Greek alphabet, in its last flowering, gave birth to the Cyrillic alphabet still used in Russia.

*

Indo-European Languages

"The Common Source" of William Jones (1746-1794) includes Sanskrit and Pali from India, Singhalese from Ceylon, Persian, Armenian, Albanian and Bulgarian; Polish, Russian and other Slavic tongues; Greek, Latin and all European languages except Estonian, Finnish, Lapp, Magyar and Basque. Similarly the Vedic pantheon echoes the Eddic of Iceland and the Olympian Greek: both Vedic hymns and Homeric hymns.

THE YEHUDIT ALPHABET

"The Common Source" of William Jones (1746-1794) includes Sanskrit and Pali from India, Singhalese from Ceylon, Persian, Armenian, Albanian and Bulgarian; Polish, Russian and other Slavic tongues; Greek, Latin and all European languages except Estonian, Finnish, Lapp, Magyar and Basque. Similarly the Vedic pantheon echoes the Eddic of Iceland and the Olympian Greek: both Vedic hymns and Homeric hymns.

*

THE YEHUDIT ALPHABET

There are in fact two (see * below) Yehudit alphabets, with some letters repeated but others entirely different. The alphabet that is used in the Tanach, and today in books and newspapers - the one on the computer keyboard illustrated at the top of this page - is called, logically enough, the Print Alphabet, and is the one used throughout TheBibleNet. For daily use, modern Ivrit has developed a second alphabet known as "Cursive", curiously enough a development back from late Aramaic - curiously because Aramaic originally used the Yehudit Print Alphabet, which evolved into the original Arabic alphabet, which was then replaced by the Persian alphabet, which was then adopted as the late Aramaic.

*(two should really be five, because the ways of writing have gone through many changes down the centuries, and scholars today need to be able to read a Qumran scroll and a Rashi commentary, a Tel Aviv newspaper and a Masoretic Torah)

The Roman alphabet that we use does the same - one alphabet for Upper Case and another for Lower Case, with some identical letters (C/c, I/i, O/o, W/w etc), some that are recognisable as variants (B/b, F/f, K/k etc) and others that seem to bear no resemblance (E/e, G/g, T/t etc). The difference between the Roman and the Yehudit is that Roman actually uses both alphabets simultaneously, where the Yehudit uses only one at a time, changing by purpose - a scribbled preparatory note in cursive, the final document in print.

The Yehudit alphabet consists of twenty-two letters, some of which may be called "consonants", others "vowels", although this Latin distinction does not properly exist in the Semitic languages; strictly all twenty-two are consonants. Of these twenty-two, five (Kaf/כ, Mem/מ, Nun/נ, Pay/פ and Tsadi/צ) change their form when they appear as the last letter of a word (thus כ/ך, מ/ם, נ/ן, פ/ף, צ/ץ) and six (Bet/ב, Gimmel/ג, Dalet/ד, Kaf/כ, Pay/פ, Tav/ת), have an alternate "soft" form (Vet, Kimmel, Talet, Chaf, Phay, Sav), although only three of these (Vet, Chaf and Phay) are still retained in contemporary usage; and in normal writing the difference is not made clear. The letters Sheen (ש) are Seen (ש) are closely related, and written identically without "pointing", but are in fact distinct letters; in Aramaic the Sheen was interchanged with Tav and vice versa (as in Yehudit Shemesh/שמש, Aramaic Tammuz/תמוז, Greek Thomas; all meaning "the sun").

We must presume that the similarity of the written letters was a late development after the interchange of the sounds, as the script form is totally different from the "printed" form. Probably what is now the "script" for both represented one of the letters, and what is now the "printed" form represented the other. It is also possible, indeed likely, that the letter Seen (ש), which does not appear in Aramaic or Assyrian, was an equivalent of Samech (ס); since we know that the script forms of the letters Samech (ס) and Ayin (ע) became interchanged, and that Samech became a circle-shape or full-moon shape, it seems reasonable to connect the moon-shape of Samech with the meaning of Sin, who was the Egyptian moon-god. This would suggest the Seen was an Egyptian letter introduced at a later stage; the fact that it has no numerical value further strengthens this thesis.

Other letters have likewise become interchanged, or are in other ways interconnected. The pronunciation of Bet (ב) is extremely similar to the correct pronunciation of Pay (פ), to the degree that Arabic speakers as opposed to European Jews have great difficulty in distinguishing the two. In the same way Tet (ט) and Tav (ת), Ayin (ע) and Aleph (א), Chet (ח) and Chaf (כ), Kaf (כ) and Kuph (ק) are often difficult to distinguish aurally (as in English a hard "c" is difficult to distinguish from a "k", and a soft "c" from an "s").

In ancient Yehudit manuscripts Nun (נ) is represented by what is now the letter for Lamed (ל), Tet (ט) by Tav (ת), Lamed (ל) by Tet (ט), and Samech (ס) by Ayin (ע); it is not clear when the transitions took place. All Yehudit letters have both script and "printed" forms; newspapers, books, texts of the scriptures etc all invariably use the "printed" form - whence its name. The script, again from its name, is used today, as it was historically, for brief notes, letters etc.

THE YEHUDIT LANGUAGE

As a language, both classical and modern Yehudit are known and understood by only a tiny number of people; yet hundreds of millions live their lives through the belief in doctrines and creeds whose roots are in the Yehudit Tanach. It may seem incomprehensible that, during two thousand years of Christianity, virtually no one has gone back to the original Yehudit and tried to understand Christianity through the authentic text, rather than relying on translations (which are frequently, and sometimes crucially, mis-translations); the rare exceptions, like Fra Roger Bacon in the 13th century, were incarcerated as heretics for their trouble. An understanding of the Ezraic Tanach makes Christianity very clear in its sources, beliefs and history; the Christianity of Jesus, which did not survive, as well as that of Paul, which did. Recognising that readers will find the Yehudit inaccessible, TheBibleNet has presented the Yehudit text at all times in transliteration as well as in the original, using a system of phonetics of its own creation.

A Note on the Yehudit:

The Yehudit language is a dialect of Amoritic or Kena'anite, and is very closely related to a number of other Semitic languages. Written Yehudit, which post-dates spoken Yehudit by many years, was originally pictographic, but developed, through the Ugaritic, into a letter-form. Each letter has a meaning. As is still the case today, Yehudit was written down without what we would consider vowels (let alone stress or even punctuation marks!); although much later, in composing the Masoretic text, a system known an "nekudot" or "pointing" was developed; one version intended as a guide to pronunciation, the other as "trope", a guide for singing the text in religious service. Each of the "nekudot" also has a meaning, and throughout the textual commentaries attention is paid to the "nekudot", rendering them when relevant in the given text, frequently questioning or challenging them in the annotations (see, and more importantly hear the "nekudot" here).

To see how difficult the process is, imagine the following text, familiar enough in its full version, but written here without vowels or punctuation, as an English equivalent of a typical phrase in the Tanach:

T B R NT T B THT S TH QSTN WHTHR TS NBLR N TH MND T SFFR TH SLNGS ND RRWS F TRGS FRTN R T TK RMS GNST S F TRBL

which of course is the opening of Hamlet's most famous soliloquy: "To be or not to be, that is the question? Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles."

At some point in history, combinations of any two of these letters were developed, in a system of "mishkalim" or weights. It is probable that the meanings of the letters were combined as well as the sounds, and it may be possible to read the meanings of two-letter roots by the meanings of their two root letters.

Fully developed classical Yehudit, while retaining many two-letter roots, is usually triliteral, combining three letters as sounds, and less often because more complicated the meanings of the three combined letters (endless puns and poems can be found that do precisely this). In modern Yehudit some four letter roots have been developed, always using the same process of "mishkalim" (leshachpetz, letagber etc); this did occasionally happen in classical Yehudit, but was extremely rare. Words containing four-letter roots in classical Yehudit can usually be reckoned to be of non-Yehudit origin, or signify two words abbreviated into one (eg Avram from Av-Ram).

Yehudit letters also have numerical values, and regularly bi-literal, and occasionally tri-literal words, are built from the combined numerical values of the letters (e.g. the goddess Yah, from the letters Yud + Hey which makes 15, which is the date in the month at which the moon is full; i.e. the principal holy day of the Bnwy Yisra-El moon-worshiping calendar; the verb "lehiyot" = to be, evolves likewise from this. Because the name of the goddess cannot be pronounced or written down, it is frequently altered to Tu = Tet/9 + Vav/6 = 15. The name Tuval (as in Tuval-Kayin) probably derives from this, as Tu + Ba'al, in the same manner as Avram from Av-Ram).

From these two or three-letter roots all Yehudit grammar is established, again according to "mishkalim". There is no real concept of time, but only of actions, all of which stem from the Creation itself, some of which have been finished, some of which have not yet: the proper explanation for the past tense being presented in the forms of Imperfect, Perfect and Pluperfect. From this come the "binyanim", the structures that break action down into simple active, simple passive, intensive, causative, reflexive and so on; similarly nouns and adjectives are formed according to set patterns, and all have the two or three letter root as their base. To understand any Yehudit word, one needs only to unhitch the "mishkalim", whether prefix, suffix or interposed letter, and, like a detective, deduce the meaning from whichever "mishkalim" and "binyanim" have been appended to the root.

THE YEHUDIT LANGUAGE

As a language, both classical and modern Yehudit are known and understood by only a tiny number of people; yet hundreds of millions live their lives through the belief in doctrines and creeds whose roots are in the Yehudit Tanach. It may seem incomprehensible that, during two thousand years of Christianity, virtually no one has gone back to the original Yehudit and tried to understand Christianity through the authentic text, rather than relying on translations (which are frequently, and sometimes crucially, mis-translations); the rare exceptions, like Fra Roger Bacon in the 13th century, were incarcerated as heretics for their trouble. An understanding of the Ezraic Tanach makes Christianity very clear in its sources, beliefs and history; the Christianity of Jesus, which did not survive, as well as that of Paul, which did. Recognising that readers will find the Yehudit inaccessible, TheBibleNet has presented the Yehudit text at all times in transliteration as well as in the original, using a system of phonetics of its own creation.

A Note on the Yehudit:

The Yehudit language is a dialect of Amoritic or Kena'anite, and is very closely related to a number of other Semitic languages. Written Yehudit, which post-dates spoken Yehudit by many years, was originally pictographic, but developed, through the Ugaritic, into a letter-form. Each letter has a meaning. As is still the case today, Yehudit was written down without what we would consider vowels (let alone stress or even punctuation marks!); although much later, in composing the Masoretic text, a system known an "nekudot" or "pointing" was developed; one version intended as a guide to pronunciation, the other as "trope", a guide for singing the text in religious service. Each of the "nekudot" also has a meaning, and throughout the textual commentaries attention is paid to the "nekudot", rendering them when relevant in the given text, frequently questioning or challenging them in the annotations (see, and more importantly hear the "nekudot" here).

To see how difficult the process is, imagine the following text, familiar enough in its full version, but written here without vowels or punctuation, as an English equivalent of a typical phrase in the Tanach:

T B R NT T B THT S TH QSTN WHTHR TS NBLR N TH MND T SFFR TH SLNGS ND RRWS F TRGS FRTN R T TK RMS GNST S F TRBL

which of course is the opening of Hamlet's most famous soliloquy: "To be or not to be, that is the question? Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, or to take arms against a sea of troubles."

At some point in history, combinations of any two of these letters were developed, in a system of "mishkalim" or weights. It is probable that the meanings of the letters were combined as well as the sounds, and it may be possible to read the meanings of two-letter roots by the meanings of their two root letters.

Fully developed classical Yehudit, while retaining many two-letter roots, is usually triliteral, combining three letters as sounds, and less often because more complicated the meanings of the three combined letters (endless puns and poems can be found that do precisely this). In modern Yehudit some four letter roots have been developed, always using the same process of "mishkalim" (leshachpetz, letagber etc); this did occasionally happen in classical Yehudit, but was extremely rare. Words containing four-letter roots in classical Yehudit can usually be reckoned to be of non-Yehudit origin, or signify two words abbreviated into one (eg Avram from Av-Ram).

Yehudit letters also have numerical values, and regularly bi-literal, and occasionally tri-literal words, are built from the combined numerical values of the letters (e.g. the goddess Yah, from the letters Yud + Hey which makes 15, which is the date in the month at which the moon is full; i.e. the principal holy day of the Bnwy Yisra-El moon-worshiping calendar; the verb "lehiyot" = to be, evolves likewise from this. Because the name of the goddess cannot be pronounced or written down, it is frequently altered to Tu = Tet/9 + Vav/6 = 15. The name Tuval (as in Tuval-Kayin) probably derives from this, as Tu + Ba'al, in the same manner as Avram from Av-Ram).

From these two or three-letter roots all Yehudit grammar is established, again according to "mishkalim". There is no real concept of time, but only of actions, all of which stem from the Creation itself, some of which have been finished, some of which have not yet: the proper explanation for the past tense being presented in the forms of Imperfect, Perfect and Pluperfect. From this come the "binyanim", the structures that break action down into simple active, simple passive, intensive, causative, reflexive and so on; similarly nouns and adjectives are formed according to set patterns, and all have the two or three letter root as their base. To understand any Yehudit word, one needs only to unhitch the "mishkalim", whether prefix, suffix or interposed letter, and, like a detective, deduce the meaning from whichever "mishkalim" and "binyanim" have been appended to the root.

Thus, for example, the word "Yitkatvu" - יתכתבו. The opening yud (י) is a prefix indicating third person masculine singular of the imperfect; but the suffix vav (ו) re-weights this into a plural of the same type; therefore we can read the "mishkal" as "they will"; the Tav (ת) second letter after a Yud tells us that the "binyan" is "hitpa'el" or reflexive ("to each other" or "to themselves"), leaving the root-word Katav (כתב) = "to write". Put this together and we have "They will write to each other", or "they will correspond". No other meaning of "Yitkatvu" is possible, and one may always approach Yehudit in this manner, solving a meaning like a mathematician and noting quod est demonstrandum at the end. All explanations in this work are based on such mathematical detective work, an empirical method which is, so to speak, infinitely verifiable.

Thus, for example, the word "Yitkatvu" - יתכתבו. The opening yud (י) is a prefix indicating third person masculine singular of the imperfect; but the suffix vav (ו) re-weights this into a plural of the same type; therefore we can read the "mishkal" as "they will"; the Tav (ת) second letter after a Yud tells us that the "binyan" is "hitpa'el" or reflexive ("to each other" or "to themselves"), leaving the root-word Katav (כתב) = "to write". Put this together and we have "They will write to each other", or "they will correspond". No other meaning of "Yitkatvu" is possible, and one may always approach Yehudit in this manner, solving a meaning like a mathematician and noting quod est demonstrandum at the end. All explanations in this work are based on such mathematical detective work, an empirical method which is, so to speak, infinitely verifiable.It should be noted that some argument exists today as to whether two-letter roots may also be grouped together in weights, with the third letter then added as a later development of the language. This is in fact highly likely, and the theory is applied throughout this work, though never assuming it to be proven correct.

At different phases in its history the language underwent considerable changes, and by the Ezraic period Aramaic had replaced Yehudit as the principal spoken language of the people, with Classical Yehudit serving much as Latin did in late mediaeval Europe. Much Aramaic appears in the Tanach, especially in the book of Ezra himself. It is therefore reasonable to deduce that differences between the two languages may have crept into the texts, particularly the interchanging of letters such as Sheen and Tav and the addition of Alephs at the beginning to make a four-letter root out of a three-letter Yehudit root (anyone familiar with the Kaddish, which is entirely in Aramaic, will recognise this distinction).

It is important for students to understand that Yehudit ceased to be a spoken language, by anyone in the world, at the time of the Babylonian exile, between 586 and 536 BCE. From then on Aramaic replaced Yehudit as the language of the Yehudim of Kena'an, so that, by the time of Jesus and the Talmudic Rabbis, Yehudit was to them what Latin is to us today, a language that we might feel it useful, even in some circumstances necessary to know, but not for daily use. Today huge numbers of Jews will sit in synagogue, reciting prayers and listening to the readings from the Tanach, with no comprehension whatsoever - and this has been the case amongst all but the most religious for centuries. Jews have spoken whatever language their host-nation spoke, or developed their own languages, such as Yiddish and Ladino, mixing some Yehudit with that host-tongue. Indeed, when Eliezer ben Yehudah set about resurrecting Yehudit as a spoken language, in Palestine in the 1880s, he was initially mocked, and told he was wasting his time. Yehudit was regarded as a dead language, even among Jews, even among the most committed Zionists. Yet today Ivrit is the national language of Israel - though there are still many who insist on Yiddish and Ladino.

Copyright © 2015 David Prashker

All rights reserved

The Argaman Press

It appears you took the time to write what I've been searching for for years. Thank you!!

ReplyDelete